5.1 Conventional Observables and Correlation Functions

[228.1.1] Table 2 gives an overview of several

geometric properties for the four microstructures

discussed in the previous section.

[228.1.2] Samples GF and SA were constructed to have the same

correlation function as sample EX.

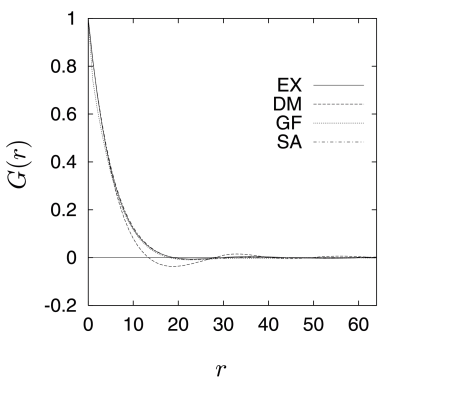

[228.1.3] Figure 7 shows the directionally averaged

correlation functions

Gr=Gr,0,0+G0,r,0+G0,0,r/3 of all four microstructures

where the notation Gr1,r2,r3=Gr was used.

[228.2.1] The Gaussian field reconstruction GGFr is

not perfect and differs from GEXr for small r.

[228.2.2] The discrepancy at small r reflects the quality of the linear

filter, and it is also responsible for the differences of the

porosity and specific internal surface.

[228.2.3] Also, by construction, GGFr is not expected to

equal GEXr for r larger than 30.

[228.2.4] Although the reconstruction method of sample SSA is

intrinsically anisotropic the correlation function of

sample SA agrees also in the diagonal directions with that

of sample EX.

[228.2.5] Sample SDM while matching the porosity and

grain size distribution was not constructed to match

also the correlation function.

[228.2.6] As a consequence GDMr differs clearly from the rest.

[228.2.7] It reflects the grain structure of the model by becoming

negative.

[228.2.8] GDMr is also anisotropic.

[page 229, §1]

[229.1.1] If two samples have the same correlation function

they are expected to have also the same specific

internal surface as calculated from

| S=-4ϕ1-ϕdGrdrr=0. | | (67) |

[229.1.2] The specific internal surface area calculated from this

formula is given in Table 2 for all four

microstructures.

[229.2.1] If one defines a decay length by the first zero

of the correlation function then the decay length

is roughly 18a for samples EX, GF and SA.

[229.2.2] For sample DM it is somewhat smaller mainly in the x-

and y-direction.

[229.2.3] The correlation length, which will be of the order of the decay

length, is thus relatively large compared

to the system size.

[229.2.4] Combined with the fact that the percolation threshold for continuum

systems is typically around 0.15 this might explain why models

GF and SA are connected in spite of their low value of the porosity.

[229.3.1] In summary, the samples SGF and SSA were

constructed to be indistinguishable with respect to

porosity and correlations from SEX.

[229.3.2] Sample SA comes close to this goal.

[229.3.3] The imperfection of the reconstruction method for

sample GF accounts for the deviations of its

correlation function at small r from that of sample EX.

[229.3.4] Although the difference in

porosity and specific surface is much bigger between

samples SA and GF than between samples SA and

EX sample SA is in fact more similar to GF than

to EX in a way that can be quantified using local

porosity analysis.

[229.3.5] Traditional characteristics such as porosity,

specific surface and correlation functions are insufficient

to distinguish different microstructures.

[229.3.6] Visual inspection of the pore space

indicates that samples GF and SA have a similar

structure which, however, differs from the structure

of sample EX.

[229.3.7] Although sample DM resembles sample EX more closely

with respect to surface roughness it differs visibly

in the shape of the grains.

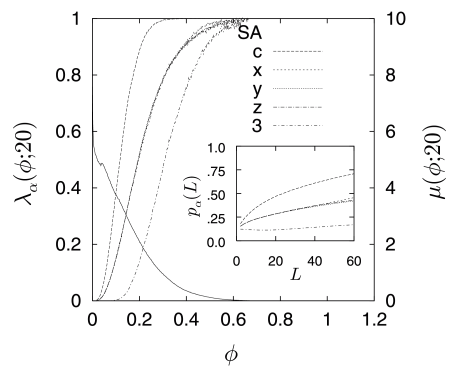

5.2 Local Porosity Analysis

[229.3.8] The differences in visual appearance of the four

microstructures can be quantified using the geometric

observables μ and λ from local porosity theory.

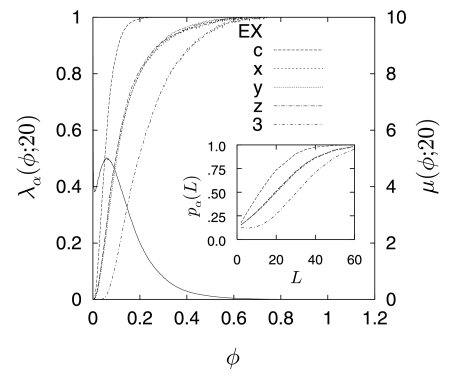

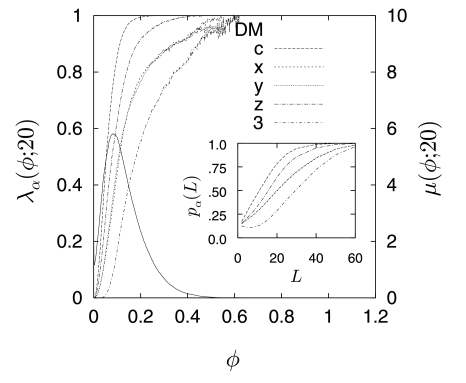

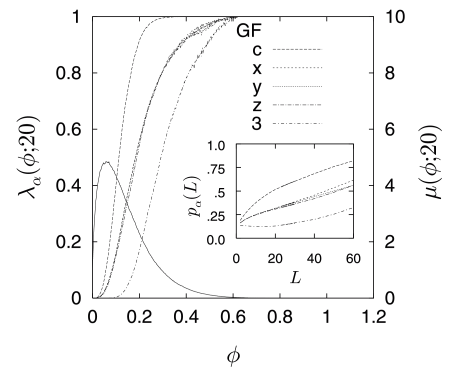

[229.3.9] The local porosity distributions μϕ,20 of the four samples

at L=20a are displayed as the solid lines in Figures

8a through 8d.

[229.3.10] The ordinates for these curves are plotted on the right vertical

axis.

[229.4.1] The figures show that the original sample exhibits stronger

porosity fluctuations than the three model samples except for

sample SA which comes close.

[229.4.2] Sample DM has the narrowest distribution which

indicates that it is most homogeneous.

[229.4.3] Figures 8a–8d show also that the δ-function

component at the origin, μ0,20, is largest for sample EX, and

smallest for sample GF.

[229.4.4] For samples DM and SA the values of μ0,20 are intermediate

and comparable.

[229.4.5] Plotting μ0,L as a function of L shows that

this remains true for all L.

[229.4.6] These results indicate that the experimental sample EX is

more strongly heterogeneous than the models, and that large

regions of matrix space occur more frequently in sample EX.

[229.4.7] A similar conclusion may be drawn from the variance of

local porosity

[page 232, §0]

fluctuations which will be studied below.

[232.0.1] The conclusion is also consistent with the results for L*

shown in Table 2.

[232.0.2] L* gives the sidelength of the largest cube that can be

fit into matrix space, and thus

L* may be viewed as a measure for the size of the largest grain.

[232.0.3] Table 2 shows that the experimental sample has a larger

L* than all the models.

[232.0.4] It is interesting to note that plotting μ1,L versus

L also shows that the curve for the experimental sample

lies above those for the other samples for all L.

[232.0.5] Thus, also the size of the largest pore and the pore space

heterogeneity are largest for sample EX.

[232.0.6] If μϕ,L* is plotted for all four samples one

finds two groups.

[232.0.7] The first group is formed by samples EX and DM,

the second by samples GF and SA.

[232.0.8] Within each group the curves μϕ,L* nearly overlap,

but they differ strongly between them.

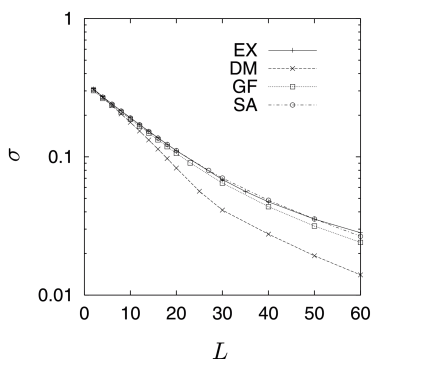

[232.1.1] Figures 9, and 10 exhibit the

dependence of the local porosity fluctuations on L.

[232.1.2] Figure 9 shows the variance of the local

porosity fluctuations, defined in (40) as function

of L.

[232.1.3] The variances for all samples indicate an approach to a

δ-distribution according to (43).

[232.1.4] Again sample DM is most homogeneous in the sense that

its variance is smallest.

[232.1.5] The agreement between samples EX, GF and SA reflects the

agreement of their correlation functions, and is expected

by virtue of eq. (40).

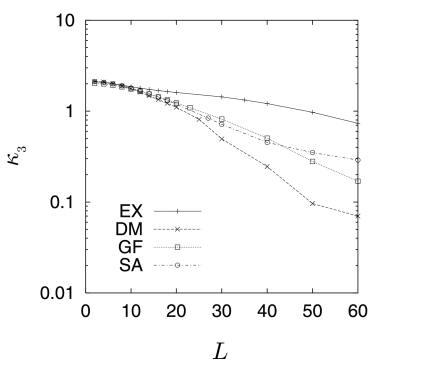

[232.1.6] Figure 10 shows the skewness as a function of L calculated from

(41).

[232.1.7] κ3 characterizes the asymmetry of the distribution,

and the difference between the most probable local

porosity and its average.

[232.1.8] Again samples GF and SA behave similarly, but sample DM and

sample EX differ from each other, and from the rest.

[page 233, §1]

[233.1.1] At L=4a the local porosity distributions μϕ,4

show small spikes at equidistantly spaced porosities for

samples EX and DM, but not for samples GF and SA.

[233.1.2] The spikes indicate that models EX and DM have a smoother

surface than models GF and SA.

[233.1.3] For smooth surfaces

and small measurement cell size porosities

corresponding to an interface intersecting the measurement

cell produce a finite probability for certain porosities

because the discretized interface allows only certain

volume fractions.

[233.1.4] In general whenever a certain porosity occurrs with

finite probability this leads to spikes in μ.

5.3 Local Percolation Analysis

[233.1.5] Visual inspection of Figures 1 through 4

does not reveal the degree of connectivity of

the various samples.

[233.1.6] A quantitative characterization of connectivity is

provided by local percolation probabilities

[27, 10], and

it is here that the samples differ most dramatically.

[233.2.1] The samples EX, DM , GF and SA are globally connected in all

three directions.

[233.2.2] This, however, does not imply that they have similar

connectivity.

[233.2.3] The last line in Table 2 gives the fraction of blocking

cells at the porosity 0.1355 and for L*.

[233.2.4] It gives a first indication that the connectivity of samples DM and GF

is, in fact, much poorer than that of the experimental sample EX.

[233.3.1] Figures 8a through 8d give a more complete

account of the situation by exhibiting λαϕ,20

for α=3,c,x,y,z for all four samples.

[233.3.2] First one notes that sample DM is strongly anisotropic in its

connectivity.

[233.3.3] It has a higher connectivity

[page 234, §0]

in the z-direction than

in the x- or y-direction.

[234.0.1] This was found to be partly due to the coarse grid used in the

sedimentation algorithm [47].

[234.0.2] λzϕ,20 for sample DM differs from that of sample EX

although their correlation functions in the z-direction are

very similar.

[234.0.3] The λ-functions for samples EX and DM rise much

more rapidly than those for samples GF and SA.

[234.0.4] The inflection point of the λ-curves for samples

EX and DM is much closer to the most probable porosity

(peak) than in samples GF and SA.

[234.0.5] All of this indicates that connectivity in

cells with low porosity is higher for samples EX and DM than

for samples GF and SA.

[234.0.6] In samples GF and SA only cells with high porosity are

percolating on average.

[234.0.7] In sample DM the curves λx,λy and λ3

show strong fluctuations for λ≈1 at values

of ϕ much larger than the ϕ or ϕSDM.

[234.0.8] This indicates a large number of high porosity cells which are

nevertheless blocked.

[234.0.9] The reason for this is perhaps that the linear compaction process

in the underlying model blocks

horizontal pore throats and decreases horizontal spatial continuity

more effectively than in the vertical direction, as shown in

[4], Table 1 p. 142.

[234.1.1] The absence of spikes in μϕ,4 for samples GF and SA combined

with the fact that cells with average porosity (≈0.135)

are rarely percolating suggests that these samples have a random

morphology similar to percolation.

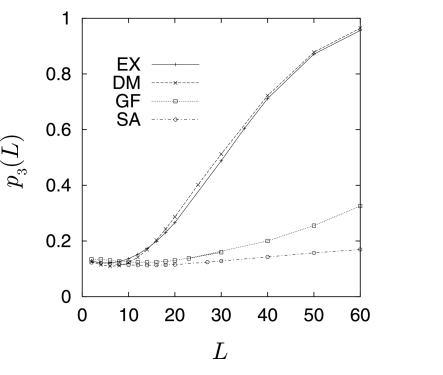

[234.2.1] The insets in Figures 8a through 8d show the

functions pαL=λαϕ,L¯ for

α=3,x,y,z,c for each sample calculated from (53).

[234.2.2] The curves for samples EX and DM are similar but differ

from those for samples GF and SA.

[234.2.3] Figure 11 exhibits the curves p3L of all

four samples in a single figure.

[234.2.4] The samples fall into two groups {EX,DM} and {GF,SA}

that behave very differently.

[234.2.5] Figure 11

[page 235, §0]

suggests that reconstruction methods

[1, 70] based on correlation functions

do not reproduce the connectivity properties of porous media.

[235.0.1] As a consequence, one expects that also the physical transport

properties will differ from the experimental sample,

and it appears questionable whether a pure correlation

function reconstruction can produce reliable models for the prediction

of transport.

[235.1.1] Preliminary results [42] indicate that these conclusions

remain unaltered if the linear and/or spherical contact

distribution are incorporated into the simulated annealing reconstruction.

[235.1.2] It was suggested in [70] that the linear contact

distribution should

improve the connectivity properties of the reconstruction,

but the reconstructions performed by [42] seem not

to confirm this expectation.