5 Results

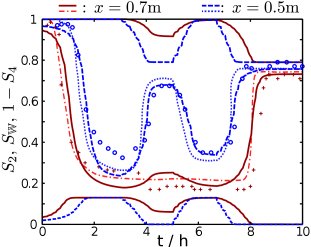

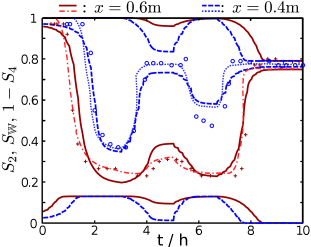

[681.1.11.1] The results of the simulations are compared with experimental data

and

the most sophisticated model of [15] (previously

developed in [22, 17]) in

Fig. 3 and 4.

[681.1.11.2] Figure 3 shows the computed time evolution of ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() at

at ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() as continuous and dashed lines.

[681.1.11.3] The experimental data for

as continuous and dashed lines.

[681.1.11.3] The experimental data for ![]() are shown as plus signs and

circles and the simulation results with the most sophisticated

model of [15] are represented by dash-dotted and

dotted curves.

[681.1.11.4] There is good qualitative agreement at all four positions.

are shown as plus signs and

circles and the simulation results with the most sophisticated

model of [15] are represented by dash-dotted and

dotted curves.

[681.1.11.4] There is good qualitative agreement at all four positions.

|

|

[681.1.12.1] During the first two hours of the experiment, the saturation decreases

because of the lowered pressure in the water reservoir.

[681.1.12.2] The instants at which the capillary fringe passes the measurement

points agree at all four points between simulation and measurement.

[681.1.12.3] The decrease in water saturation induces a production of non-percolating water.

[681.1.12.4] The corresponding decrease in non-percolating air is not visible in the graph

because of the small amount of initial non-percolating air.

[681.1.12.5] The pressure does not change between ![]() and

and ![]() .

[681.1.12.6] Hence, the rate of saturation change decreases

and saturation reaches an almost stationary value.

[681.1.12.7] The calculated water saturations of that plateau

are slightly smaller than the experimental ones.

[681.1.12.8] Measured and predicted values during the first increase of the reservoir pressure

at around

.

[681.1.12.6] Hence, the rate of saturation change decreases

and saturation reaches an almost stationary value.

[681.1.12.7] The calculated water saturations of that plateau

are slightly smaller than the experimental ones.

[681.1.12.8] Measured and predicted values during the first increase of the reservoir pressure

at around

![]() show good agreement excluding

show good agreement excluding

![]() .

[681.1.12.9] In contrast to the simulated saturation, the measured saturation

decreases at

.

[681.1.12.9] In contrast to the simulated saturation, the measured saturation

decreases at

![]() after an increase of the pressure at the lower boundary.

[681.1.12.10] This surprising effect was not

discussed in the experimental work [15] and the lack

of error bars makes an interpretation difficult (similar experiments

[16] by the same authors suggest error bars of order

after an increase of the pressure at the lower boundary.

[681.1.12.10] This surprising effect was not

discussed in the experimental work [15] and the lack

of error bars makes an interpretation difficult (similar experiments

[16] by the same authors suggest error bars of order

![]() ).

[681.1.12.11] The increase of water saturation induces a decrease

of non-percolating water and a production non-percolating air.

).

[681.1.12.11] The increase of water saturation induces a decrease

of non-percolating water and a production non-percolating air.

[681.1.13.1] The subsequent evolution of the saturation shows qualitatively similar phenomena upon changing the pressure. [681.1.13.2] Note, that the spatiotemporal evolution of the saturation requires an infinite number of scanning curves in traditional hysteresis modelling, i.e. when the process changes between drainage and imbibibtion as a function of time and position. [681.1.13.3] Here in our model a single set of parameters is sufficient, and there is no need to know scanning curves beforehand. [681.1.13.4] At the end of the experiment water is almost completely connected at all four measurement positions, while most of the air is disconnected and trapped. [681.1.13.5] The trapped air prevents the complete filling of the column with water and indicates the irreversibility of the process.

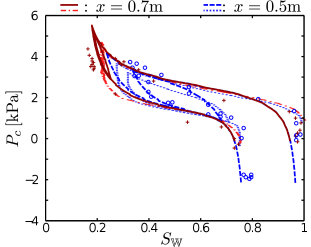

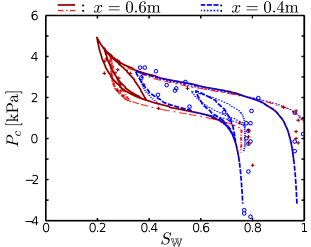

[681.1.14.1] Figure 4 illustrate the hysteretic drainage and

imbibition processes in the ![]() plane.

[681.1.14.2] It shows

plane.

[681.1.14.2] It shows ![]() obtained by eliminating

obtained by eliminating ![]() and

and ![]() from the measurements of

from the measurements of ![]() and

and ![]() at

at ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() .

[681.1.14.3] The lines of the simulations indicate the time evolution

which is compared to the time discrete observations in the experiment.

[681.1.14.4] Experimental and simulated data agree qualitatively.

[681.1.14.5] The values at

.

[681.1.14.3] The lines of the simulations indicate the time evolution

which is compared to the time discrete observations in the experiment.

[681.1.14.4] Experimental and simulated data agree qualitatively.

[681.1.14.5] The values at ![]() corresponds to the minimum in the pressure

protocol of the water reservoir (see Figure 1) at the start of the experiment.

[681.1.14.6] The decrease in water saturation induces an increase in

corresponds to the minimum in the pressure

protocol of the water reservoir (see Figure 1) at the start of the experiment.

[681.1.14.6] The decrease in water saturation induces an increase in ![]() during the

primary drainage and the curves of all four positions coincide with

the experimental data.

[681.1.14.7] The point with the lowest saturation of each primary drainage branch

corresponds to the instant when the pressure in the water reservoir is increased again.

[681.1.14.8] The deviations between simulation and experiment at

during the

primary drainage and the curves of all four positions coincide with

the experimental data.

[681.1.14.7] The point with the lowest saturation of each primary drainage branch

corresponds to the instant when the pressure in the water reservoir is increased again.

[681.1.14.8] The deviations between simulation and experiment at ![]() and

and ![]() originate from the mismatched saturations (see Fig. 3).

[681.1.14.9] The following imbibition discloses the hysteretic nature of the process

as the curves at the four different positions follow different scanning curves.

[681.1.14.10] Also the subsequent drainage yields different drainage scanning curves.

[681.1.14.11] This branch of the curve is difficult to identify in the experimental data

at

originate from the mismatched saturations (see Fig. 3).

[681.1.14.9] The following imbibition discloses the hysteretic nature of the process

as the curves at the four different positions follow different scanning curves.

[681.1.14.10] Also the subsequent drainage yields different drainage scanning curves.

[681.1.14.11] This branch of the curve is difficult to identify in the experimental data

at ![]() and

and ![]() but matches well at the other two locations.

The final imbibition yields saturation

but matches well at the other two locations.

The final imbibition yields saturation ![]() and the curves at all

four positions almost coincide again.

and the curves at all

four positions almost coincide again.

|

|

[681.1.15.1] The figures show that the quality of our results is comparable to the most sophisticated model used in [15]. [681.1.15.2] However, in our theory the hysteresis in saturation profiles is due to the natural assumption that breakup and coalescence rates are proportional to the rate and direction of saturation change, whereas in their models, the hysteresis is nonlocal in time and inserted directly by hand into the constitutive functions. [681.1.15.3] The good quality of the results is surprising because it is evident that some of our assumptions such as the incompressibility of air and the incompressible porous medium are questionable. [681.1.15.4] We remark also, that the lack of error bars for the experimental data makes an interpretation difficult.