Appendix C Distributions

[page 65, §1]

[65.1.1] Distributions are generalized functions [31].

[65.1.2] They were invented to overcome

the differentiability requirements for functions in analysis

and mathematical physics [105, 63].

[65.1.3] Distribution theory has also a physical origin.

[65.1.4] A physical observable ![]() can never be measured at a point

can never be measured at a point ![]() because

every measurement apparatus averages over a small volume

around

because

every measurement apparatus averages over a small volume

around ![]() [115].

[65.1.5] This ‘‘smearing out’’ can be modelled as an integration

with smooth ‘‘test functions’’ having compact support.

[115].

[65.1.5] This ‘‘smearing out’’ can be modelled as an integration

with smooth ‘‘test functions’’ having compact support.

[65.2.1] Let ![]() denote the space of admissible test functions.

[65.2.2] Commonly used test function spaces are

denote the space of admissible test functions.

[65.2.2] Commonly used test function spaces are

![]() , the space of infinitely often differentiable

functions,

, the space of infinitely often differentiable

functions,

![]() ,

the space of smooth functions with compact support (see (B.5)),

,

the space of smooth functions with compact support (see (B.5)),

![]() ,

the space of smooth functions vanishing at infinity (see (B.3)),

or the so called Schwartz space

,

the space of smooth functions vanishing at infinity (see (B.3)),

or the so called Schwartz space ![]() of smooth functions

decreasing rapidly at infinity (see (B.21)).

of smooth functions

decreasing rapidly at infinity (see (B.21)).

[65.3.1] A distribution ![]() is a linear and continuous mapping that maps

is a linear and continuous mapping that maps

![]() to a real (

to a real (![]() )

or complex (

)

or complex (![]() ) number

12 (This is a footnote:) 12For vector valued distributions see [106].

[65.3.2] There exists a canonical correspondence

between functions and distributions.

[65.3.3] More precisely, for every locally integrable function

) number

12 (This is a footnote:) 12For vector valued distributions see [106].

[65.3.2] There exists a canonical correspondence

between functions and distributions.

[65.3.3] More precisely, for every locally integrable function

![]() there exists a distribution

there exists a distribution ![]() (often also denoted with the same symbol

(often also denoted with the same symbol ![]() )

defined by

)

defined by

| (C.1) |

for every test function ![]() .

[65.3.4] Distributions that can be written in this way are called

regular distributions.

[65.3.5] Distributions that are not regular are sometimes called singular.

[65.3.6] The mapping

.

[65.3.4] Distributions that can be written in this way are called

regular distributions.

[65.3.5] Distributions that are not regular are sometimes called singular.

[65.3.6] The mapping ![]() that assigns to a locally

integrable

that assigns to a locally

integrable ![]() its associated distribution is injective and

continuous.

[65.3.7] The set of distributions is again a vector space, namely

the dual space of the vector space of test functions, and

it is denoted as

its associated distribution is injective and

continuous.

[65.3.7] The set of distributions is again a vector space, namely

the dual space of the vector space of test functions, and

it is denoted as ![]() where

where ![]() is the test function

space.

is the test function

space.

[page 66, §1]

[66.1.1] Important examples for singular distributions are the

Dirac ![]() -function and its derivatives.

[66.1.2] They are defined by the rules

-function and its derivatives.

[66.1.2] They are defined by the rules

| (C.2) | |||

| (C.3) |

for every test function ![]() and

and ![]() .

[66.1.3] Clearly,

.

[66.1.3] Clearly, ![]() is not a function, because if it were a

function, then

is not a function, because if it were a

function, then ![]() would have to hold.

[66.1.4] Another example for a singular distribution is

the finite part or principal value

would have to hold.

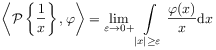

[66.1.4] Another example for a singular distribution is

the finite part or principal value ![]() of

of ![]() .

[66.1.5] It is defined by

.

[66.1.5] It is defined by

|

(C.4) |

for ![]() .

[66.1.6] It is a singular distribution on

.

[66.1.6] It is a singular distribution on ![]() , but regular on

, but regular on

![]() where it coincides

with the function

where it coincides

with the function ![]() .

.

[66.2.1] Equation (C.2) illustrates how distributions circumvent the limitations of differentiation for ordinary functions. [66.2.2] The basic idea is the formula for partial integration

| (C.5) |

valid for ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

,

![]() and

and ![]() an open set.

[66.2.3] The formula is proved by extending

an open set.

[66.2.3] The formula is proved by extending ![]() as

as ![]() to all

of

to all

of ![]() and using Leibniz’ product rule.

[66.2.4] Rewriting the formula as

and using Leibniz’ product rule.

[66.2.4] Rewriting the formula as

| (C.6) |

suggests to view ![]() again as a linear continuous

mapping (integral) on a space

again as a linear continuous

mapping (integral) on a space ![]() of test functions

of test functions

![]() .

[66.2.5] Then the formula is a rule for differentiating

.

[66.2.5] Then the formula is a rule for differentiating ![]() given that

given that ![]() is differentiable.

is differentiable.

[66.3.1] Distributions on the test function space ![]() are called tempered distributions.

[66.3.2] The space of tempered distributions is the dual space

are called tempered distributions.

[66.3.2] The space of tempered distributions is the dual space

![]() .

[66.3.3] Tempered distributions generalize locally integrable

functions growing at most polynomially for

.

[66.3.3] Tempered distributions generalize locally integrable

functions growing at most polynomially for ![]() .

[66.3.4] All distributions with compact support are tempered.

Square integrable functions are tempered distributions.

[66.3.5] The derivative of a tempered distribution is again a

tempered distribution.

[66.3.6]

.

[66.3.4] All distributions with compact support are tempered.

Square integrable functions are tempered distributions.

[66.3.5] The derivative of a tempered distribution is again a

tempered distribution.

[66.3.6] ![]() is dense in

is dense in ![]() for all

for all ![]() but not in

but not in ![]() .

[66.3.7] The Fourier transform and its inverse are continous maps of

the Schwartz space onto itself.

[66.3.8] A distribution

.

[66.3.7] The Fourier transform and its inverse are continous maps of

the Schwartz space onto itself.

[66.3.8] A distribution ![]() belongs to

belongs to ![]() if and

only if it is the derivative of a continuous function with slow

growth, i.e. it is of the form

if and

only if it is the derivative of a continuous function with slow

growth, i.e. it is of the form

![]()

[page 67, §0]

where ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() is a bounded

continuous function on

is a bounded

continuous function on ![]() .

[67.0.1] Note that the exponential function is not a tempered distribution.

.

[67.0.1] Note that the exponential function is not a tempered distribution.

[67.1.1] A distribution ![]() is said to have

compact support

if there exists a compact subset

is said to have

compact support

if there exists a compact subset ![]() such that

such that

![]() for all test functions

with

for all test functions

with ![]() .

[67.1.2] The Dirac

.

[67.1.2] The Dirac ![]() -function is an example.

[67.1.3]

Other examples are Radon measures on a compact set

-function is an example.

[67.1.3]

Other examples are Radon measures on a compact set ![]() .

[67.1.4] They can be described as linear functionals

on

.

[67.1.4] They can be described as linear functionals

on ![]() .

[67.1.5] If the set

.

[67.1.5] If the set ![]() is sufficiently regular (e.g. if it is the

closure of a region with piecewise smooth boundary)

then every distribution with compact support in

is sufficiently regular (e.g. if it is the

closure of a region with piecewise smooth boundary)

then every distribution with compact support in ![]() can be written in the form

can be written in the form

| (C.7) |

where ![]() ,

, ![]() is a multiindex,

is a multiindex,

![]() and

and ![]() are continuous functions of

compact support.

[67.1.6] Here

are continuous functions of

compact support.

[67.1.6] Here ![]() and the partial derivatives in

and the partial derivatives in ![]() are

distributional derivatives defined above.

[67.1.7] A special case are distributions with support in a single

point taken as

are

distributional derivatives defined above.

[67.1.7] A special case are distributions with support in a single

point taken as ![]() .

[67.1.8] Any such distributions can be written in the form

.

[67.1.8] Any such distributions can be written in the form

| (C.8) |

where ![]() is the Dirac

is the Dirac ![]() -function and

-function and ![]() are constants.

are constants.

[67.2.1] The multiplication of a distribution ![]() with a smooth function

with a smooth function ![]() is defined by the formula

is defined by the formula

![]() where

where ![]() .

[67.2.2] A combination of multiplication by a smooth function

and differentiation allows to define differential

operators

.

[67.2.2] A combination of multiplication by a smooth function

and differentiation allows to define differential

operators

| (C.9) |

with smooth ![]() .

[67.2.3] They are well defined for all distributions in

.

[67.2.3] They are well defined for all distributions in

![]() .

.

[67.3.1] A distribution is called homogeneous of degree ![]() if

if

| (C.10) |

for all ![]() .

[67.3.2] Here

.

[67.3.2] Here ![]() is the standard definition.

[67.3.3] The Dirac

is the standard definition.

[67.3.3] The Dirac ![]() -distribution is homogeneous of degree

-distribution is homogeneous of degree ![]() .

[67.3.4] For regular distributions the definition coincides with

homogeneity of functions

.

[67.3.4] For regular distributions the definition coincides with

homogeneity of functions ![]() .

[67.3.5] The convolution kernels

.

[67.3.5] The convolution kernels ![]() from eq. (2.39)

are homogeneous of degree

from eq. (2.39)

are homogeneous of degree ![]() .

[67.3.6] Homogeneous distributions remain homogeneous under

differentiation.

[67.3.7] A homogeneous locally integrable function

.

[67.3.6] Homogeneous distributions remain homogeneous under

differentiation.

[67.3.7] A homogeneous locally integrable function ![]() on

on ![]() of degree

of degree ![]() can be extended to homogeneous distributions

can be extended to homogeneous distributions ![]() on all

of

on all

of ![]() .

[67.3.8] The degree of homogeneity of

.

[67.3.8] The degree of homogeneity of ![]() must again be

must again be ![]() .

[67.3.9] As long as

.

[67.3.9] As long as ![]() the integral

the integral

| (C.11) |

[page 68, §0]

which converges absolutely for ![]() can be

used to define

can be

used to define ![]() by analytic continuation

from the region

by analytic continuation

from the region ![]() to the point

to the point ![]() .

[68.0.1] For

.

[68.0.1] For ![]() , however, this is not

always possible.

[68.0.2] An example is the function

, however, this is not

always possible.

[68.0.2] An example is the function ![]() on

on ![]() .

[68.0.3] It cannot be extended to a homogeneous distribution of degree

.

[68.0.3] It cannot be extended to a homogeneous distribution of degree ![]() on all of

on all of ![]() .

.

[68.1.1] For ![]() and

and ![]() their tensor product is the function

their tensor product is the function ![]() defined on

defined on ![]() .

[68.1.2] The function

.

[68.1.2] The function ![]() gives a functional

gives a functional

| (C.12) |

for ![]() .

[68.1.3] For two distributions this formula defines the their tensor product.

[68.1.4] An example is a measure

.

[68.1.3] For two distributions this formula defines the their tensor product.

[68.1.4] An example is a measure ![]() concentrated on the

surface

concentrated on the

surface ![]() in

in ![]() where

where ![]() is a measure

on

is a measure

on ![]() .

[68.1.5] The convolution of distribution defined in the main text (see eq.

(2.52) can then be defined by the formula

.

[68.1.5] The convolution of distribution defined in the main text (see eq.

(2.52) can then be defined by the formula

| (C.13) |

whenever one of the distributions ![]() or

or ![]() has compact support.

has compact support.