2.2 Mathematical Introduction to Fractional Derivatives

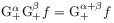

[22.1.1] The brief historical introduction has shown that fractional derivatives may be defined in numerous ways. [22.1.2] A natural and frequently used approach starts from repeated integration and extends it to fractional integrals. [22.1.3] Fractional derivatives are then defined either by continuation of fractional integrals to negative order (following Leibniz’ ideas [73]), or by integer order derivatives of fractional integrals (as suggested by Riemann [96]).

2.2.1 Fractional Integrals

2.2.1.1 Iterated Integrals

[22.2.1] Consider a locally integrable1 (This is a footnote:) 1

A function ![]() is called locally integrable if

it is integrable on all compact subsets

is called locally integrable if

it is integrable on all compact subsets ![]() (see eq.(B.9)).

real valued function

(see eq.(B.9)).

real valued function

![]() whose domain of definition

whose domain of definition

![]() is an interval with

is an interval with

![]() .

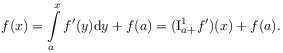

[22.2.2] Integrating

.

[22.2.2] Integrating

[page 23, §0]

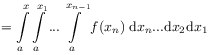

![]() times gives the fundamental formula

times gives the fundamental formula

|

|||

|

(2.27) |

where ![]() and

and ![]() .

[23.0.1] This formula may be proved by induction.

[23.0.2] It reduces

.

[23.0.1] This formula may be proved by induction.

[23.0.2] It reduces ![]() -fold integration to a single

convolution integral (Faltung).

[23.0.3] The subscript

-fold integration to a single

convolution integral (Faltung).

[23.0.3] The subscript ![]() indicates that the integration

has

indicates that the integration

has ![]() as its lower limit.

[23.0.4] An analogous formula holds with

lower limit

as its lower limit.

[23.0.4] An analogous formula holds with

lower limit ![]() and upper limit

and upper limit ![]() .

[23.0.5] In that case the subscript

.

[23.0.5] In that case the subscript ![]() will be used.

will be used.

2.2.1.2 Riemann-Liouville Fractional Integrals

[23.1.1] Equation (2.27) for ![]() -fold

integration can be generalized to

noninteger values of

-fold

integration can be generalized to

noninteger values of ![]() using the relation

using the relation

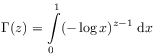

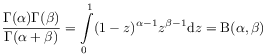

![]() where

where

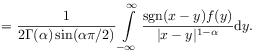

|

(2.28) |

is Euler’s ![]() -function

defined for all

-function

defined for all ![]() .

.

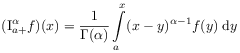

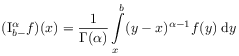

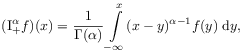

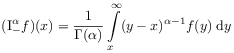

Definition 2.1

[23.2.1] Let ![]() .

[23.2.2] The Riemann-Liouville fractional integral of order

.

[23.2.2] The Riemann-Liouville fractional integral of order ![]() with lower limit

with lower limit ![]() is defined for locally integrable functions

is defined for locally integrable functions ![]() as

as

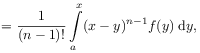

|

(2.29a) | |

| for | ||

|

(2.29b) | |

for ![]() .

[23.2.4] For

.

[23.2.4] For ![]()

| (2.30) |

completes the definition.

[23.2.5] The definition may be generalized to ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

[page 24, §1]

[24.1.1] Formula (2.29a) appears in

[96, p.363] with ![]() and in

[76, p.8] with

and in

[76, p.8] with ![]() .

[24.1.2] The notation is not standardized.

[24.1.3] Leibniz, Lagrange and Liouville used the

symbol

.

[24.1.2] The notation is not standardized.

[24.1.3] Leibniz, Lagrange and Liouville used the

symbol ![]() [73, 22, 76],

Grünwald wrote

[73, 22, 76],

Grünwald wrote ![]() ,

while Riemann used

,

while Riemann used ![]() [96]

and Most wrote

[96]

and Most wrote ![]() [89].

[24.1.4] The notation in (2.29) is that of [99, 98, 54, 52].

[24.1.5] Modern authors also use

[89].

[24.1.4] The notation in (2.29) is that of [99, 98, 54, 52].

[24.1.5] Modern authors also use ![]() [37],

[37],

![]() [97],

[97],

![]() [94],

[94],

![]() [23],

[23],

![]() [85, 102, 91], or

[85, 102, 91], or

![]() [92]

instead of

[92]

instead of ![]() 2 (This is a footnote:) 2

Some authors [97, 26, 92, 23, 85, 91] employ the

derivative symbol

2 (This is a footnote:) 2

Some authors [97, 26, 92, 23, 85, 91] employ the

derivative symbol ![]() also for integrals, resp.

also for integrals, resp. ![]() for derivatives, to

emphasize the similarity between fractional

integration and differentiation.

If this is done, the choice of Riesz and Feller,

namely

for derivatives, to

emphasize the similarity between fractional

integration and differentiation.

If this is done, the choice of Riesz and Feller,

namely ![]() , seems superior

in the sense that fractional derivatives, similar to integrals, are

nonlocal operators, while integer derivatives are local operators..

, seems superior

in the sense that fractional derivatives, similar to integrals, are

nonlocal operators, while integer derivatives are local operators..

[24.2.1] The fractional integral operators ![]() are commonly

called Riemann-Liouville fractional integrals [99, 98, 94]

although sometimes this name is reserved for

the case

are commonly

called Riemann-Liouville fractional integrals [99, 98, 94]

although sometimes this name is reserved for

the case ![]() [85].

[24.2.2] Their domain of definition is typically chosen

as

[85].

[24.2.2] Their domain of definition is typically chosen

as ![]() or

or

![]() [99, 98, 94].

[24.2.3] For the definition of Lebesgue spaces see the Appendix B.

[24.2.4] If

[99, 98, 94].

[24.2.3] For the definition of Lebesgue spaces see the Appendix B.

[24.2.4] If ![]() then

then ![]() and

and ![]() is finite for almost all

is finite for almost all ![]() .

[24.2.5] If

.

[24.2.5] If ![]() with

with ![]() and

and

![]() then

then ![]() is finite for all

is finite for all ![]() .

[24.2.6] Analogous statements hold for

.

[24.2.6] Analogous statements hold for ![]() [98].

[98].

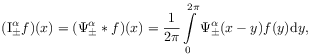

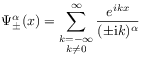

2.2.1.3 Weyl Fractional Integrals

[24.4.1] Examples (2.5) and (2.6) or

(A.3) and (A.5)

show that Definition 2.1 is well suited for

fractional integration of power series, but not for

functions defined by Fourier series.

[24.4.2] In fact, if ![]() is a periodic function with period

is a periodic function with period ![]() ,

and3 (This is a footnote:) 3The notation

,

and3 (This is a footnote:) 3The notation ![]() indicates that the sum does not need

to converge, and, if it converges, does not need to

converge to

indicates that the sum does not need

to converge, and, if it converges, does not need to

converge to ![]() .

.

| (2.31) |

then the Riemann-Liouville fractional ![]() will

in general not be periodic.

[24.4.3] For this reason an alternative definition of

fractional integrals was investigated by Weyl [124].

will

in general not be periodic.

[24.4.3] For this reason an alternative definition of

fractional integrals was investigated by Weyl [124].

[24.5.1] Functions on the unit circle ![]() correspond to

correspond to ![]() -periodic functions on the real line.

[24.5.2] Let

-periodic functions on the real line.

[24.5.2] Let ![]() be periodic with period

be periodic with period ![]() and such that

the integral of

and such that

the integral of ![]() over the interval

over the interval ![]() vanishes,

so that

vanishes,

so that ![]() in eq. (2.31).

[24.5.3] Then the integral of

in eq. (2.31).

[24.5.3] Then the integral of ![]() is itself a periodic function,

and the constant of integration can be chosen such that

the integral over

is itself a periodic function,

and the constant of integration can be chosen such that

the integral over ![]() vanishes again.

[24.5.4] Repeating the integration

vanishes again.

[24.5.4] Repeating the integration ![]() times one finds

using (2.6) and the integral representation

times one finds

using (2.6) and the integral representation

[page 25, §0]

![]() of Fourier coefficients

of Fourier coefficients

|

(2.32) |

with ![]() .

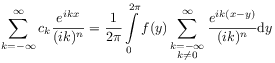

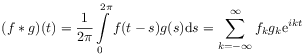

[25.0.1] Recall the convolution formula [132, p.36]

.

[25.0.1] Recall the convolution formula [132, p.36]

|

(2.33) |

for two periodic functions

![]() and

and

![]() .

[25.0.2] Using eq. (2.33)

and generalizing (2.32)

to noninteger

.

[25.0.2] Using eq. (2.33)

and generalizing (2.32)

to noninteger ![]() suggests the following definition.

[99, 94].

suggests the following definition.

[99, 94].

Definition 2.2

[25.1.1] Let ![]() be periodic

with period

be periodic

with period ![]() and such that its integral over a

period vanishes.

[25.1.2] The Weyl fractional integral of order

and such that its integral over a

period vanishes.

[25.1.2] The Weyl fractional integral of order ![]() is

defined as

is

defined as

|

(2.34) |

where

|

(2.35) |

for ![]() .

.

[25.2.1] It can be shown that the series for ![]() converges

and that the Weyl definition coincides with the

Riemann-Liouville definition [133]

converges

and that the Weyl definition coincides with the

Riemann-Liouville definition [133]

|

(2.36a) | |

| respectively | ||

|

(2.36b) | |

for ![]() periodic functions whose integral over

a period vanishes.

[25.2.2] This is eq. (2.29) with

periodic functions whose integral over

a period vanishes.

[25.2.2] This is eq. (2.29) with ![]() resp.

resp. ![]() .

[25.2.3] For this reason the Riemann-Liouville

.

[25.2.3] For this reason the Riemann-Liouville

[page 26, §0]

fractional

integrals with limits ![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() ,

are often called Weyl fractional integrals

[24, 99, 85, 94].

,

are often called Weyl fractional integrals

[24, 99, 85, 94].

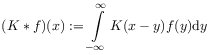

[26.1.1] The Weyl fractional integral may be rewritten as a convolution

| (2.37) |

where the convolution product for

functions on ![]() is defined as4 (This is a footnote:) 4

If

is defined as4 (This is a footnote:) 4

If ![]() then

then ![]() exists for almost all

exists for almost all ![]() and

and ![]() .

[26.1.2] If

.

[26.1.2] If ![]() ,

, ![]() with

with

![]() and

and ![]() then

then

![]() , the space of continuous functions

vanishing at infinity.

, the space of continuous functions

vanishing at infinity.

|

(2.38) |

and the convolution kernels are defined as

| (2.39) |

for ![]() .

[26.1.3] Here

.

[26.1.3] Here

| (2.40) |

is the Heaviside unit step function,

and ![]() with the convention that

with the convention that

![]() is real for

is real for ![]() .

[26.1.4] For

.

[26.1.4] For ![]() the kernel

the kernel

| (2.41) |

is the Dirac ![]() -function defined in (C.2)

in Appendix C.

[26.1.5] Note that

-function defined in (C.2)

in Appendix C.

[26.1.5] Note that ![]() for

for ![]() .

.

2.2.1.4 Riesz Fractional Integrals

[26.2.1] Riemann-Liouville and Weyl fractional integrals have upper or lower limits of integration, and are sometimes called left-sided resp. right-sided integrals. [26.2.2] A more symmetric definition was advanced in [97].

Definition 2.3

[26.3.1] Let ![]() be locally integrable.

[26.3.2] The Riesz fractional integral or Riesz potential

of order

be locally integrable.

[26.3.2] The Riesz fractional integral or Riesz potential

of order ![]() is defined as the linear combination [99]

is defined as the linear combination [99]

|

(2.42) |

[27.1.1] Riesz fractional integration may be written as a convolution

| (2.45a) | |||

| (2.45b) |

with the (one-dimensional) Riesz kernels

| (2.46) |

for ![]() , and

, and

| (2.47) |

for ![]() .

[27.1.2] Subsequently, Feller introduced the

generalized Riesz-Feller kernels [26]

.

[27.1.2] Subsequently, Feller introduced the

generalized Riesz-Feller kernels [26]

| (2.48) |

with parameter ![]() .

[27.1.3] The corresponding generalized

Riesz-Feller fractional integral of order

.

[27.1.3] The corresponding generalized

Riesz-Feller fractional integral of order ![]() and type

and type ![]() is defined as

is defined as

| (2.49) |

[27.1.4] This formula interpolates continuously from the Weyl integral

![]() for

for ![]() through the Riesz integral

through the Riesz integral

![]() for

for ![]() to the Weyl integral

to the Weyl integral

![]() for

for ![]() .

[27.1.5] Due to their symmetry Riesz-Feller fractional

integrals are readily generalized to higher dimensions.

.

[27.1.5] Due to their symmetry Riesz-Feller fractional

integrals are readily generalized to higher dimensions.

[page 28, §1]

2.2.1.5 Fractional Integrals of Distributions

[28.1.1] Fractional integration can be extended to distributions

using the convolution formula (2.37) above.

[28.1.2] Distributions are generalized functions [105, 31].

[28.1.3] They are defined as linear functionals on a space ![]() of

conveniently chosen ‘‘test functions’’.

[28.1.4] For every locally integrable function

of

conveniently chosen ‘‘test functions’’.

[28.1.4] For every locally integrable function

![]() there exists a distribution

there exists a distribution ![]() defined by

defined by

|

(2.50) |

where ![]() is test function from a suitable space

is test function from a suitable space

![]() of test functions.

[28.1.5] By abuse of notation one often writes

of test functions.

[28.1.5] By abuse of notation one often writes

![]() for the associated distribution

for the associated distribution ![]() .

[28.1.6] Distributions that correspond to functions via (2.50)

are called regular distributions.

[28.1.7] Examples for regular distributions are

the convolution kernels

.

[28.1.6] Distributions that correspond to functions via (2.50)

are called regular distributions.

[28.1.7] Examples for regular distributions are

the convolution kernels ![]() defined in (2.39).

[28.1.8] They are locally integrable functions on

defined in (2.39).

[28.1.8] They are locally integrable functions on ![]() when

when ![]() .

[28.1.9] Distributions that are not regular are sometimes called singular.

[28.1.10] An important example for a singular distribution is the

Dirac

.

[28.1.9] Distributions that are not regular are sometimes called singular.

[28.1.10] An important example for a singular distribution is the

Dirac ![]() -function.

[28.1.11] It is defined as

-function.

[28.1.11] It is defined as ![]()

| (2.51) |

for every test function ![]() .

[28.1.12] The test function space

.

[28.1.12] The test function space ![]() is usually chosen as a

subspace of

is usually chosen as a

subspace of ![]() , the space of

infinitely differentiable functions.

[28.1.13] A brief introduction to distributions is given in

Appendix C.

, the space of

infinitely differentiable functions.

[28.1.13] A brief introduction to distributions is given in

Appendix C.

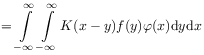

[28.2.1] In order to generalize (2.37) to distributions

one must define the convolution of two distributions.

[28.2.2] To do so one multiplies eq. (2.38) on both sides

with a smooth test function ![]() of

compact support.

[28.2.3] Integrating gives

of

compact support.

[28.2.3] Integrating gives

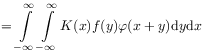

|

|||

|

|||

| (2.52) |

where the notation ![]() means that the functional

means that the functional ![]() is applied to the function

is applied to the function

![]() for fixed

for fixed ![]() .

[28.2.4] Explicitly, for fixed

.

[28.2.4] Explicitly, for fixed ![]()

|

(2.53) |

[page 29, §0]

where ![]() .

[29.0.1] Equation (2.52) can be used as a definition

for the convolution of distributions provided that the

right hand side has meaning.

[29.0.2] This is not always the case as the

counterexample

.

[29.0.1] Equation (2.52) can be used as a definition

for the convolution of distributions provided that the

right hand side has meaning.

[29.0.2] This is not always the case as the

counterexample ![]() shows.

[29.0.3] In general the convolution product is not associative

(see eq. (2.113)).

[29.0.4] However, associative and commutative convolution

algebras exist [21].

[29.0.5] Equation (2.52) is always meaningful

when

shows.

[29.0.3] In general the convolution product is not associative

(see eq. (2.113)).

[29.0.4] However, associative and commutative convolution

algebras exist [21].

[29.0.5] Equation (2.52) is always meaningful

when ![]() or

or ![]() is compact [63].

[29.0.6] Another case

is when

is compact [63].

[29.0.6] Another case

is when ![]() and

and ![]() have support in

have support in ![]() .

[29.0.7] This will be assumed in the following.

.

[29.0.7] This will be assumed in the following.

Definition 2.4

[29.1.1] Let ![]() be a distribution

be a distribution ![]() with

with ![]() .

[29.1.2] Then its fractional integral is the distribution

.

[29.1.2] Then its fractional integral is the distribution

![]() defined as

defined as

| (2.54) |

for ![]() .

[29.1.3] It has support in

.

[29.1.3] It has support in ![]() .

.

[29.2.1] If ![]() with

with ![]() then also

then also ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

2.2.1.6 Integral Transforms

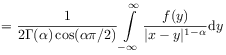

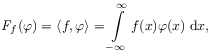

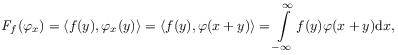

[29.3.1] The Fourier transformation is defined as

|

(2.55) |

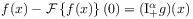

for functions ![]() .

[29.3.2] Then

.

[29.3.2] Then

| (2.56) |

holds for ![]() by virtue of the convolution theorem.

[29.3.3] The equation cannot be extended directly to

by virtue of the convolution theorem.

[29.3.3] The equation cannot be extended directly to ![]() because the Fourier integral on the left hand side may not

exist.

[29.3.4] Consider e.g.

because the Fourier integral on the left hand side may not

exist.

[29.3.4] Consider e.g. ![]() and

and ![]() .

[29.3.5] Then

.

[29.3.5] Then ![]() const as

const as ![]() and

and

![]() does not exist [94].

[29.3.6] Equation (2.56) can be extended to all

does not exist [94].

[29.3.6] Equation (2.56) can be extended to all ![]() with

with

![]() for functions in the so called Lizorkin space

[99, p.148] defined as the space of functions

for functions in the so called Lizorkin space

[99, p.148] defined as the space of functions ![]() such that

such that ![]() for all

for all ![]() .

.

[29.4.1] For the Riesz potentials one has

| (2.57a) | |||

| (2.57b) |

for functions in Lizorkin space.

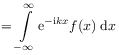

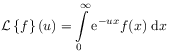

[page 30, §1] [30.1.1] The Laplace transform is defined as

|

(2.58) |

for locally integrable functions ![]() .

[30.1.2] Now

.

[30.1.2] Now

| (2.59) |

by the convolution theorem for Laplace transforms.

[30.1.3] The Laplace transform of ![]() leads to a more complicated operator.

leads to a more complicated operator.

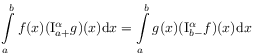

2.2.1.7 Fractional Integration by Parts

[30.2.1] If ![]() with

with ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and

![]() ,

, ![]() for

for ![]() then

the formula

then

the formula

|

(2.60) |

holds.

[30.2.2] The formula is known as fractional integration by parts [99].

[30.2.3] For ![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() the analogous formula

the analogous formula

|

(2.61) |

holds for Weyl fractional integrals.

[30.3.1] These formulae provide a second method of generalizing fractional integration to distributions. [30.3.2] Equation (2.60) may be read as

| (2.62) |

for a distribution ![]() and a test function

and a test function ![]() .

[30.3.3] It shows that right- and left-sided fractional integrals

are adjoint operators.

[30.3.4] The formula may be viewed as a definition

of the fractional integral

.

[30.3.3] It shows that right- and left-sided fractional integrals

are adjoint operators.

[30.3.4] The formula may be viewed as a definition

of the fractional integral ![]() of a distribution

provided that the operator

of a distribution

provided that the operator ![]() maps the test function

space into itself.

maps the test function

space into itself.

2.2.1.8 Hardy-Littlewood Theorem

[30.4.1] The mapping properties of convolutions can be studied

with the help of Youngs inequality.

Let ![]() obey

obey ![]() and

and

![]() .

[30.4.2] If

.

[30.4.2] If ![]() and

and ![]() then

then

![]() and Youngs inequality

and Youngs inequality

![]() holds.

[30.4.3] It follows that

holds.

[30.4.3] It follows that

![]() if

if

[page 31, §0]

![]() and

and ![]() with

with

![]() .

[31.0.1] The Hardy-Littlewood theorem states that these estimates

remain valid for

.

[31.0.1] The Hardy-Littlewood theorem states that these estimates

remain valid for ![]() although these kernels

do not belong to any

although these kernels

do not belong to any ![]() -space

[37, 38].

[31.0.2] The theorem was generalized to higher dimensions

by Sobolev in 1938, and is also known as the Hardy-Littlewood-Sobolev

inequality (see [37, 38, 113, 63]).

-space

[37, 38].

[31.0.2] The theorem was generalized to higher dimensions

by Sobolev in 1938, and is also known as the Hardy-Littlewood-Sobolev

inequality (see [37, 38, 113, 63]).

Theorem 2.5

[31.1.1] Let ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() .

[31.1.2] Then

.

[31.1.2] Then ![]() are bounded linear operators

from

are bounded linear operators

from ![]() to

to ![]() with

with ![]() ,i.e.

there exists a constant

,i.e.

there exists a constant ![]() independent of

independent of ![]() such that

such that

![]() .

.

2.2.1.9 Additivity

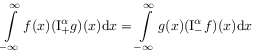

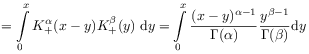

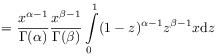

[31.2.1] The basic composition law for fractional integrals follows from

|

|||

|

|||

| (2.63) |

where Euler’s Beta-function

|

(2.64) |

was used. [31.2.2] This implies the semigroup law for exponents

| (2.65) |

also called additivity law. [31.2.3] It holds for Riemann-Liouville, Weyl and Riesz-Feller fractional integrals of functions.

2.2.2 Fractional Derivatives

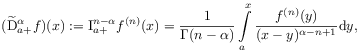

2.2.2.1 Riemann-Liouville Fractional Derivatives

[31.3.1] Riemann [96, p.341] suggested to define fractional derivatives as integer order derivatives of fractional integrals.

Definition 2.6

[31.4.1] Let ![]() .

[31.4.2] The Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative of order

.

[31.4.2] The Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative of order ![]() with lower limit

with lower limit ![]() (resp. upper limit

(resp. upper limit ![]() )

is defined for

)

is defined for

[page 32, §0]

functions such that ![]() and

and

![]() as

as

| (2.66) |

and ![]() for

for ![]() .

[32.0.1] For

.

[32.0.1] For ![]() the definition is extended

for functions

the definition is extended

for functions ![]() with

with

![]() as

as

| (2.67) |

where5 (This is a footnote:) 5![]() is the largest integer smaller than

is the largest integer smaller than ![]() .

.

![]() is smallest integer larger than

is smallest integer larger than ![]() .

.

[32.1.1] Here ![]() denotes a Sobolev space defined in (B.17).

[32.1.2] For

denotes a Sobolev space defined in (B.17).

[32.1.2] For ![]() the space

the space ![]() coincides

with the space of absolutely continuous functions.

coincides

with the space of absolutely continuous functions.

[32.2.1] The notation for fractional derivatives is not

standardized6 (This is a footnote:) 6see footnote 2.1.

[32.2.2] Leibniz and Euler used ![]() [73, 72, 25]

Riemann wrote

[73, 72, 25]

Riemann wrote ![]() [96],

Liouville preferred

[96],

Liouville preferred ![]() [76],

Grünwald used

[76],

Grünwald used ![]() or

or

![]() [34],

Marchaud wrote

[34],

Marchaud wrote ![]() , and

Hardy-Littlewood used an index

, and

Hardy-Littlewood used an index ![]() [37].

[32.2.3] The notation in (2.67) follows [99, 98, 54, 52].

Modern authors also use

[37].

[32.2.3] The notation in (2.67) follows [99, 98, 54, 52].

Modern authors also use

![]() [97],

[97],

![]() [23],

[23],

![]() [94, 85, 102],

[94, 85, 102],

![]() [129, 102],

[129, 102],

![]() [92]

instead of

[92]

instead of ![]() .

.

[32.3.1] Let ![]() be absolutely continuous on the finite interval

be absolutely continuous on the finite interval ![]() .

[32.3.2] Then, its derivative

.

[32.3.2] Then, its derivative ![]() exists almost everywhere on

exists almost everywhere on

![]() with

with ![]() , and

the function

, and

the function ![]() can be

written as

can be

written as

|

(2.68) |

Substituting this into ![]() gives

gives

| (2.69) |

where commutativity of ![]() and

and ![]() was used.

[32.3.3] It follows that

was used.

[32.3.3] It follows that

| (2.70) |

for ![]() .

[32.3.4] Above, the notations

.

[32.3.4] Above, the notations

| (2.71) |

were used for the first order derivative.

[page 33, §1] [33.1.1] This observation suggests to introduce a modified Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative through

|

(2.72) |

where ![]() .

[33.1.2] Note, that

.

[33.1.2] Note, that ![]() must be at least

must be at least ![]() -times differentiable.

[33.1.3] Formula (2.72) is due to Liouville [76, p.10]

(see eq. (2.18) above),

but nowadays sometimes named after Caputo [17].

-times differentiable.

[33.1.3] Formula (2.72) is due to Liouville [76, p.10]

(see eq. (2.18) above),

but nowadays sometimes named after Caputo [17].

Theorem 2.7

[33.2.2] For ![]() with

with ![]() the Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative

the Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative

![]() exists almost everywhere

for

exists almost everywhere

for ![]() .

[33.2.3] It can be written as

.

[33.2.3] It can be written as

| (2.73) |

in terms of the Liouville(-Caputo) derivative defined in (2.72).

[33.3.1] The Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative is the left inverse of Riemann-Liouville fractional integrals. [33.3.2] More specifically, [99, p.44]

Theorem 2.8

[33.3.3] Let ![]() .

[33.3.4] Then

.

[33.3.4] Then

| (2.74) |

holds for all ![]() with

with ![]() .

.

[33.4.1] For the right inverses of fractional integrals one finds

Theorem 2.9

[33.4.2] Let ![]() and

and ![]() .

[33.4.3] If in addition

.

[33.4.3] If in addition ![]() where

where

![]() then

then

| (2.75) |

holds.

[33.4.4] For ![]() this becomes

this becomes

| (2.76) |

[33.5.1] The last theorem implies that for ![]() and

and ![]() with

with

![]() the equality

the equality

| (2.77) |

[page 34, §0] holds only if

| (2.78a) | ||

| and | ||

| (2.78b) | ||

for all ![]() .

[34.0.1] Note that the existence of

.

[34.0.1] Note that the existence of ![]() in

eq. (2.77) does not imply that

in

eq. (2.77) does not imply that ![]() can be

written as

can be

written as ![]() for some integrable function

for some integrable function ![]() [99].

[34.0.2] This holds only if both conditions (2.78) are satisfied.

[34.0.3] As an example where one of them fails, consider

the function

[99].

[34.0.2] This holds only if both conditions (2.78) are satisfied.

[34.0.3] As an example where one of them fails, consider

the function ![]() for

for ![]() .

[34.0.4] Then

.

[34.0.4] Then ![]() exists.

[34.0.5] Now

exists.

[34.0.5] Now ![]() so that

(2.78b) fails.

[34.0.6] There does not

exist an integrable

so that

(2.78b) fails.

[34.0.6] There does not

exist an integrable ![]() such that

such that ![]() .

[34.0.7] In fact,

.

[34.0.7] In fact, ![]() corresponds to the

corresponds to the ![]() -distribution

-distribution ![]() .

.

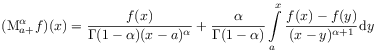

2.2.2.2 General Types of Fractional Derivatives

[34.1.1] Riemann-Liouville fractional derivatives have been generalized in [52, p.433] to fractional derivatives of different types.

Definition 2.10

[34.2.1] The generalized Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative of order

![]() and type

and type ![]() with lower (resp. upper) limit

with lower (resp. upper) limit ![]() is defined as

is defined as

| (2.79) |

for functions such that the expression on the right hand side exists.

[34.3.1] The type ![]() of a fractional derivative allows to

interpolate continuously from

of a fractional derivative allows to

interpolate continuously from ![]() to

to ![]() .

[34.3.2] A relation between fractional derivatives of the same order

but different types was given in [52, p.434].

.

[34.3.2] A relation between fractional derivatives of the same order

but different types was given in [52, p.434].

2.2.2.3 Marchaud-Hadamard Fractional Derivatives

[34.4.1] Marchaud’s approach [78] is based on Hadamards finite parts of divergent integrals [36]. [34.4.2] The strategy is to define fractional derivatives as analytic continuation of fractional integrals to negative orders. [see [99, p.225]]

Definition 2.11

[34.5.1] Let ![]() and

and ![]() .

[34.5.2] The

Marchaud fractional derivative of order

.

[34.5.2] The

Marchaud fractional derivative of order ![]() with lower limit

with lower limit ![]() is defined as

is defined as

|

(2.80) |

[page 35, §0]

and the

Marchaud fractional derivative of order ![]() with upper limit

with upper limit ![]() is defined as

is defined as

|

(2.81) |

[35.0.1] For ![]() (resp.

(resp. ![]() ) the definition is

) the definition is

|

(2.82) |

[35.0.2] The definition is completed with ![]() for all

variants.

for all

variants.

[35.1.1] The idea of Marchaud’s method is to extend

the Riemann-Liouville integral from ![]() to

to ![]() ,

and to define

,

and to define

|

(2.83) |

where ![]() .

[35.1.2] However, this is not possible because the

integral in (2.83) diverges.

[35.1.3] The idea is to subtract the divergent part of the integral,

.

[35.1.2] However, this is not possible because the

integral in (2.83) diverges.

[35.1.3] The idea is to subtract the divergent part of the integral,

| (2.84) |

obtained by setting ![]() for

for ![]() .

[35.1.4] Subtracting (2.83) from (2.84) for

.

[35.1.4] Subtracting (2.83) from (2.84) for

![]() suggests the definition

suggests the definition

|

(2.85) |

[35.1.5] Formal integration by parts leads to ![]() ,

showing that this definition contains the Riemann-Liouville

definition.

,

showing that this definition contains the Riemann-Liouville

definition.

[35.2.1] The definition may be extended to ![]() in two ways.

[35.2.2] The first consists in applying (2.85) to the

in two ways.

[35.2.2] The first consists in applying (2.85) to the ![]() -th

derivative

-th

derivative ![]() for

for ![]() .

[35.2.3] The second possibility is to regard

.

[35.2.3] The second possibility is to regard ![]() as

a first order difference, and to generalize to

as

a first order difference, and to generalize to ![]() -th order

differences.

[35.2.4] The

-th order

differences.

[35.2.4] The ![]() -th order difference is

-th order difference is

| (2.86) |

where ![]() is the identity operator and

is the identity operator and

| (2.87) |

[page 36, §0]

is the translation operator.

[36.0.1] The Marchaud fractional derivative can then be

extended to ![]() through [94, 98]

through [94, 98]

|

(2.88) |

where

|

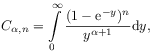

(2.89) |

where the limit may be taken in the sense of pointwise or norm convergence.

[36.1.1] The Marchaud derivatives ![]() are defined for a wider class of functions than

Weyl derivatives

are defined for a wider class of functions than

Weyl derivatives ![]() .

[36.1.2] As an example consider the function

.

[36.1.2] As an example consider the function ![]() const.

const.

[36.2.1] Let ![]() be such that there exists a function

be such that there exists a function

![]() with

with ![]() .

[36.2.2] Then

the Riemann-Liouville derivative and

the Marchaud derivative coincide almost everywhere, i.e.

.

[36.2.2] Then

the Riemann-Liouville derivative and

the Marchaud derivative coincide almost everywhere, i.e.

![]() for almost

all

for almost

all ![]() [99, p.228].

[99, p.228].

2.2.2.4 Weyl Fractional Derivatives

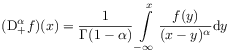

[36.3.1] There are two kinds of Weyl fractional derivatives for periodic functions. [36.3.2] The Weyl-Liouville fractional derivative is defined as [99, p.351],[94]

| (2.90) |

for ![]() where the Weyl integral

where the Weyl integral ![]() was defined

in (2.34).

[36.3.3] The Weyl-Marchaud fractional derivative is defined

as [99, p.352],[94]

was defined

in (2.34).

[36.3.3] The Weyl-Marchaud fractional derivative is defined

as [99, p.352],[94]

(y)\mathrm{d}y](mi/mi121.png) |

(2.91) |

for ![]() where

where ![]() is defined in eq. (2.35).

[36.3.4] The Weyl derivatives are defined for periodic functions of with zero mean

in

is defined in eq. (2.35).

[36.3.4] The Weyl derivatives are defined for periodic functions of with zero mean

in ![]() where

where ![]() .

[36.3.5] In this space

.

[36.3.5] In this space ![]() ,

i.e. the Weyl-Liouville and Weyl-Marchaud form coincide [99].

[36.3.6] As for fractional integrals, it can be shown that the

Weyl-Liouville derivative

,

i.e. the Weyl-Liouville and Weyl-Marchaud form coincide [99].

[36.3.6] As for fractional integrals, it can be shown that the

Weyl-Liouville derivative ![]()

|

(2.92) |

coincides with the Riemann-Liouville derivative with

lower limit ![]() .

[36.3.7] In addition one has the equivalence

.

[36.3.7] In addition one has the equivalence ![]() with the Marchaud-Hadamard fractional derivative in a suitable

sense [99, p.357].

with the Marchaud-Hadamard fractional derivative in a suitable

sense [99, p.357].

[page 37, §1]

2.2.2.5 Riesz Fractional Derivatives

[37.1.1] To define the Riesz fractional derivative as integer derivatives of Riesz potentials consider the Fourier transforms

| (2.93) |

| (2.94) |

for ![]() .

[37.1.2] Comparing this to eq. (2.57)

suggests to consider

.

[37.1.2] Comparing this to eq. (2.57)

suggests to consider

| (2.95) |

as a candidate for the Riesz fractional derivative.

[37.2.1] Following [94] the

strong Riesz fractional derivative of order ![]()

![]() of a function

of a function ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

is defined through the limit

,

is defined through the limit

| (2.96) |

whenever it exists. [37.2.2] The convolution kernel defined as

| (2.97) |

is obtained from eq. (2.95).

[37.2.3] Indeed, this definition is equivalent to eq. (2.94).

[37.2.4] A function ![]() where

where ![]() has a strong Riesz derivative of order

has a strong Riesz derivative of order ![]() if and only

if there exsists a function

if and only

if there exsists a function ![]() such that

such that

![]() .

[37.2.5] Then

.

[37.2.5] Then ![]() .

.

2.2.2.6 Grünwald-Letnikov Fractional Derivatives

[37.3.1] The basic idea of the Grünwald approach is to generalize finite difference quotients to noninteger order, and then take the limit to obtain a differential quotient. [37.3.2] The first order derivative is the limit

| (2.98) |

of a difference quotient.

[37.3.3] In the last equality ![]() is the identity operator,

and

is the identity operator,

and

| (2.99) |

is the translation operator.

[37.3.4] Repeated application of ![]() gives

gives

| (2.100) |

[page 38, §0]

where ![]() .

[38.0.1] The second order derivative can then be written as

.

[38.0.1] The second order derivative can then be written as

| (2.101) |

and the ![]() -th derivative

-th derivative

| (2.102) |

which exhibits the similarity with the binomial formula.

[38.0.2] The generalization to noninteger ![]() gives rise to

fractional difference quotients defined through

gives rise to

fractional difference quotients defined through

| (2.103) |

for ![]() .

[38.0.3] These are generally divergent for

.

[38.0.3] These are generally divergent for ![]() .

[38.0.4] For example, if

.

[38.0.4] For example, if ![]() , then

, then

| (2.104) |

diverges as ![]() if

if ![]() .

[38.0.5] Fractional difference quotients were studied in [68].

Note that fractional differences obey [99]

.

[38.0.5] Fractional difference quotients were studied in [68].

Note that fractional differences obey [99]

| (2.105) |

Definition 2.12

[38.1.1] The Grünwald-Letnikov fractional derivative of order ![]() is defined as the limit

is defined as the limit

| (2.106) |

of fractional difference quotients whenever the limit exists. [38.1.2] The Grünwald Letnikov fractional derivative is called pointwise or strong depending on whether the limit is taken pointwise or in the norm of a suitable Banach space.

[38.2.1] For a definition of Banach spaces and their norms see e.g. [128].

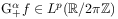

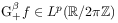

[38.3.1] The Grünwald-Letnikov fractional derivative

has been studied for periodic functions in ![]() with

with ![]() in [99, 94].

[38.3.2] It has the following properties.

in [99, 94].

[38.3.2] It has the following properties.

[page 39, §1]

Theorem 2.13

[39.1.1] Let ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() .

[39.1.2] Then the following statements are equivalent:

.

[39.1.2] Then the following statements are equivalent:

[39.1.3] There exists a function

such that

such that where

where  .

.[39.1.4] There exists a function

such that

such that holds for almost all

holds for almost all  .

.

Theorem 2.14

[39.2.1] Let ![]() ,

, ![]() and

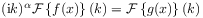

and ![]() .

[39.2.2] Then:

.

[39.2.2] Then:

implies

implies

for every

for every  .

.

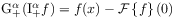

2.2.2.7 Fractional Derivatives of Distributions

[39.3.1] The basic idea for defining fractional differentiation of

distributions is to extend the definition of fractional

integration (2.54) to negative ![]() .

[39.3.2] However, for

.

[39.3.2] However, for ![]() the distribution

the distribution

![]() becomes singular because

becomes singular because ![]() is

not locally integrable in this case.

[39.3.3] The extension of

is

not locally integrable in this case.

[39.3.3] The extension of ![]() to

to ![]() requires

regularization [31, 128, 63].

[39.3.4] It turns out that the regularization exists and is

essentially unique as long as

requires

regularization [31, 128, 63].

[39.3.4] It turns out that the regularization exists and is

essentially unique as long as ![]() .

.

Definition 2.15

[39.4.1] Let ![]() be a distribution

be a distribution ![]() with

with ![]() .

[39.4.2] Then the fractional derivative of order

.

[39.4.2] Then the fractional derivative of order ![]() with lower limit

with lower limit ![]() is the distribution

is the distribution ![]() defined as

defined as

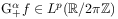

| (2.107) |

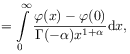

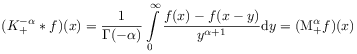

where ![]() and

and

![K_{+}^{\alpha}(x)=\begin{cases}\Theta(x)\displaystyle\frac{x^{{\alpha-1}}}{\Gamma(\alpha)}&,\mathrm{Re}\,\alpha>0\\

&\\

\displaystyle\frac{\mathrm{d}^{N}}{\mathrm{d}x^{N}}\left[\Theta(x)\displaystyle\frac{x^{{\alpha+N-1}}}{\Gamma(\alpha+N)}\right]&,\mathrm{Re}\,\alpha+N>0,N\in\mathbb{N}\end{cases}](mi/mi130.png) |

(2.108) |

is the kernel distribution.

[39.4.3] For ![]() one finds

one finds ![]() and

and ![]() as the identity operator.

[39.4.4] For the

as the identity operator.

[39.4.4] For the ![]() one finds

one finds

| (2.109) |

where ![]() is the

is the ![]() -th derivative

of the

-th derivative

of the ![]() distribution.

distribution.

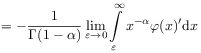

[page 40, §1] [40.1.1] The kernel distribution in (2.108) is

| (2.110) |

for ![]() .

[40.1.2] Its regularized action is

.

[40.1.2] Its regularized action is

| (2.111a) | |||

|

(2.111b) | ||

|

(2.111c) | ||

|

(2.111d) |

where ![]() was assumed in the last step

and the arbitrary constant was chosen as

was assumed in the last step

and the arbitrary constant was chosen as ![]() .

[40.1.3] This choice regularizes the divergent first term in (2.111c).

[40.1.4] If this rule is used for the distributional convolution

.

[40.1.3] This choice regularizes the divergent first term in (2.111c).

[40.1.4] If this rule is used for the distributional convolution

|

(2.112) |

then the Marchaud-Hadamard form is recovered with ![]() .

.

[40.2.1] It is now possible to show that the convolution of distributions is in general not associative. [40.2.2] A counterexample is

| (2.113) |

where ![]() is the Heaviside step function.

is the Heaviside step function.

[40.3.1] ![]() has support in

has support in ![]() .

[40.3.2] The distributions in

.

[40.3.2] The distributions in ![]() with

with ![]() form a convolution algebra [21] and

one finds [31, 99]

form a convolution algebra [21] and

one finds [31, 99]

Theorem 2.16

[40.3.3] If ![]() with

with ![]() then also

then also ![]() with

with ![]() .

[40.3.4] Moreover, for all

.

[40.3.4] Moreover, for all ![]()

| (2.114) |

with ![]() for

for ![]() .

[40.3.5] For each

.

[40.3.5] For each ![]() with

with ![]() there exists a unique distribution

there exists a unique distribution ![]() with

with ![]() such that

such that

![]() .

.

[page 41, §1] [41.1.1] Note that

| (2.115) |

for all ![]() .

[41.2.1] Also, the differentiation rule

.

[41.2.1] Also, the differentiation rule

| (2.116) |

holds for all ![]() .

[41.2.2] It contains

.

[41.2.2] It contains

| (2.117) |

for all ![]() as a special case.

as a special case.

2.2.2.8 Fractional Derivatives at Their Lower Limit

[41.3.1] All fractional derivatives defined above are nonlocal operators. [41.3.2] A local fractional derivative operator was introduced in [40, 41, 52].

Definition 2.17

[41.4.1] For ![]() the

Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative of order

the

Riemann-Liouville fractional derivative of order ![]() at the lower limit

at the lower limit ![]() is defined by

is defined by

| (2.118) |

whenever the two limits exist and are equal.

[41.4.2] If ![]() exists the function

exists the function ![]() is called

fractionally differentiable at the limit

is called

fractionally differentiable at the limit ![]() .

.

[41.5.1] These operators are useful for the analysis of singularities. [41.5.2] They were applied in [40, 41, 42, 44, 52] to the analysis of singularities in the theory of critical phenomena and to the generalization of Ehrenfests classification of phase transitions. [41.5.3] There is a close relationship to the theory of regularly varying functions [107] as evidenced by the following result [52].

Theorem 2.18

[41.6.1] Let the function ![]() be monotonously increasing with

be monotonously increasing with

![]() and

and ![]() , and such that

, and such that

![]() with

with ![]() and

and ![]() is

also monotonously increasing on a neighbourhood

is

also monotonously increasing on a neighbourhood ![]() for

small

for

small ![]() .

[41.6.2] Let

.

[41.6.2] Let ![]() , let

, let ![]() be a constant and

be a constant and

![]() a slowly varying function for

a slowly varying function for ![]() .

[41.6.3] Then

.

[41.6.3] Then

| (2.119) |

holds if and only if

| (2.120) |

holds.

[page 42, §1]

[42.1.1] A function ![]() is called slowly varying at infinity if

is called slowly varying at infinity if

![]() for all

for all ![]() .

[42.1.2] A function

.

[42.1.2] A function ![]() is called slowly varying at

is called slowly varying at ![]() if

if

![]() is slowly varying at infinity.

is slowly varying at infinity.

2.2.2.9 Fractional Powers of Operators

[42.2.1] The spectral decomposition of selfadjoint operators

is a familiar mathematical tool from quantum mechanics [116].

[42.2.2] Let ![]() denote a selfadjoint operator with domain

denote a selfadjoint operator with domain ![]() and spectral family

and spectral family ![]() on a Hilbert

space

on a Hilbert

space ![]() with scalar product

with scalar product ![]() .

[42.2.3] Then

.

[42.2.3] Then

| (2.121) |

holds for all ![]() .

[42.2.4] Here

.

[42.2.4] Here ![]() is the spectrum of

is the spectrum of ![]() .

[42.2.5] It is then straightforward to define

the fractional power

.

[42.2.5] It is then straightforward to define

the fractional power ![]() by

by

| (2.122) |

on the domain

| (2.123) |

[42.2.6] Similarly, for any measurable

function ![]() the operator

the operator ![]() is

defined with an integrand

is

defined with an integrand ![]() in eq. (2.122).

[42.2.7] This yields an operator calculus that allows to

perform calculations with functions instead of

operators.

in eq. (2.122).

[42.2.7] This yields an operator calculus that allows to

perform calculations with functions instead of

operators.

[42.3.1] Fractional powers of the Laplacian as the generator of the diffusion semigroup were introduced by Bochner [13] and Feller [26] based on Riesz’ fractional potentials. [42.3.2] The fractional diffusion equation

| (2.124) |

was related by Feller to the Levy stable laws [74] using

one dimensional fractional integrals ![]() of order

of order ![]() and type

and type ![]() [26]7 (This is a footnote:) 7Fellers motivation to

introduce the type

[26]7 (This is a footnote:) 7Fellers motivation to

introduce the type ![]() was this relation..

[42.3.3] For

was this relation..

[42.3.3] For ![]() eq. (2.124) reduces to the diffusion

equation.

[42.3.4] This type of fractional diffusion will be referred

to as fractional diffusion of Bochner-Levy type

(see Section 2.3.4 for more discussion).

[42.3.5] Later, these ideas were extended to fractional

powers of closed8 (This is a footnote:) 8

An operator

eq. (2.124) reduces to the diffusion

equation.

[42.3.4] This type of fractional diffusion will be referred

to as fractional diffusion of Bochner-Levy type

(see Section 2.3.4 for more discussion).

[42.3.5] Later, these ideas were extended to fractional

powers of closed8 (This is a footnote:) 8

An operator ![]() on a Banach space

on a Banach space ![]() is called closed if the set of pairs

is called closed if the set of pairs ![]() with

with ![]() is closed in

is closed in ![]() .

semigroup generators

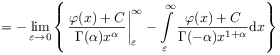

[4, 5, 69, 70].

[42.3.6] If

.

semigroup generators

[4, 5, 69, 70].

[42.3.6] If ![]() is the infinitesimal generator of a

is the infinitesimal generator of a

[page 43, §0]

semigroup

![]() (see Section 2.3.3.2 for definitions of

(see Section 2.3.3.2 for definitions of ![]() and

and ![]() ) on a Banach space

) on a Banach space ![]() then its fractional power is defined as

then its fractional power is defined as

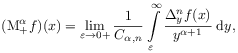

![(-\mathrm{A})^{\alpha}f=\lim _{{\varepsilon\to 0+}}\frac{1}{-\Gamma(-\alpha)}\int\limits _{\varepsilon}^{\infty}t^{{-\alpha-1}}[\mathbf{1}-T(t)]f\mathrm{d}t](mi/mi84.png) |

(2.125) |

for every ![]() for which the limit exists in the norm

of

for which the limit exists in the norm

of ![]() [120, 121, 93, 123].

[43.0.1] This aproach is clearly inspired by the Marchaud form (2.82).

Alternatively, one may use the Grünwald approach

to define fractional powers of semigroup generators [122, 99].

[120, 121, 93, 123].

[43.0.1] This aproach is clearly inspired by the Marchaud form (2.82).

Alternatively, one may use the Grünwald approach

to define fractional powers of semigroup generators [122, 99].

2.2.2.10 Pseudodifferential Operators

[43.1.1] The calculus of pseudodifferential operators represents another generalization of the operator calculus in Hilbert spaces. [43.1.2] It has its roots in Hadamard’s ideas [36], Riesz potentials [97], Feller’s suggestion [26] and Calderon-Zygmund singular integrals [16]. [43.1.3] Later it was generalized and became a tool for treating elliptic partial differential operators with nonconstant coefficients.

Definition 2.19

[43.2.1] A (Kohn-Nirenberg) pseudodifferential operator of order ![]()

![]() is defined as

is defined as

| (2.126) |

and the function ![]() is called its symbol.

[43.2.2] The symbol is in the Kohn-Nirenberg symbol class

is called its symbol.

[43.2.2] The symbol is in the Kohn-Nirenberg symbol class ![]() if it is in

if it is in ![]() , and there exists a

compact set

, and there exists a

compact set ![]() such that

such that

![]() , and for any pair

of multiindices

, and for any pair

of multiindices ![]() there is a constant

there is a constant ![]() such

that

such

that

| (2.127) |

[43.2.3] The Hörmander symbol class ![]() is obtained by

replacing the exponent

is obtained by

replacing the exponent ![]() on the right hand side

with

on the right hand side

with ![]() where

where ![]() .

.

[43.3.1] Pseudodifferential operators provide a unified approach to differential and integral or convolution operators that are ‘‘nearly’’ translation invariant. [43.3.2] They have a close relation with Weyl quantization in physics [116, 28]. However, they will not be discussed further because the traditional symbol classes do not contain the usual fractional derivative operators. [43.3.3] Fractional Riesz derivatives are not pseudodifferential operators in the sense above. [43.3.4] Their symbols do not fall into any of the standard Kohn-Nirenberg or Hörmander symbol classes due to lack of differentiability at the origin.

[page 44, §1]

2.2.3 Eigenfunctions

[44.1.1] The eigenfunctions of Riemann-Liouville fractional derivatives are defined as the solutions of the fractional differential equation

| (2.128) |

where ![]() is the eigenvalue.

[44.1.2] They are readily identifed using eq. (A.11)

as

is the eigenvalue.

[44.1.2] They are readily identifed using eq. (A.11)

as

| (2.129) |

where

| (2.130) |

is the generalized Mittag-Leffler function [125, 126].

[44.1.3] More generally the eigenvalue equation for

fractional derivatives of order ![]() and type

and type ![]() reads

reads

| (2.131) |

and it is solved by [54, eq.124]

| (2.132) |

[page 45, §0]

where the case ![]() corresponds to (2.128).

[45.0.1] A second important special case is the equation

corresponds to (2.128).

[45.0.1] A second important special case is the equation

| (2.133) |

with ![]() .

[45.0.2] In this case the eigenfunction

.

[45.0.2] In this case the eigenfunction

| (2.134) |

where ![]() is the Mittag-Leffler function

[86].

[45.0.3] The Mittag-Leffler function plays a central role

in fractional calculus.

[45.0.4] It has only recently been calculated numerically

in the full complex plane

[108, 62].

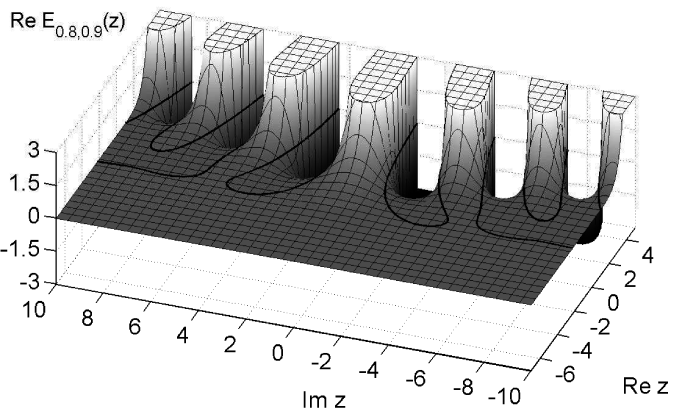

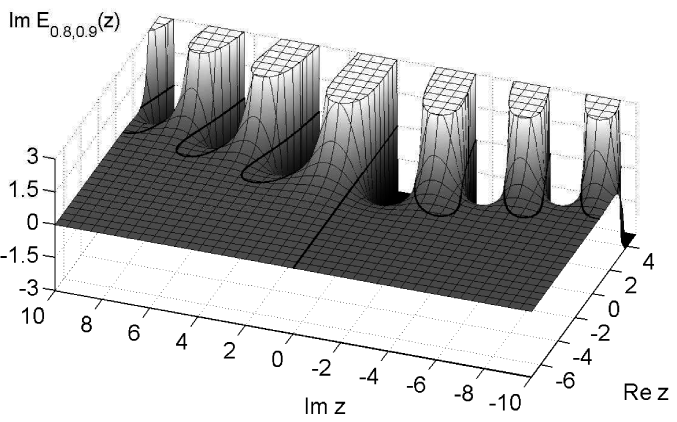

[45.0.5] Figure 2.1 and 2.2

illustrate

is the Mittag-Leffler function

[86].

[45.0.3] The Mittag-Leffler function plays a central role

in fractional calculus.

[45.0.4] It has only recently been calculated numerically

in the full complex plane

[108, 62].

[45.0.5] Figure 2.1 and 2.2

illustrate ![]() for a rectangular region in the

complex plane (see [108]).

[45.1.1] The solid line in Figure 2.1 is the line

for a rectangular region in the

complex plane (see [108]).

[45.1.1] The solid line in Figure 2.1 is the line

![]() , in Figure 2.2 it

is

, in Figure 2.2 it

is ![]() .

.

[45.2.1] Note, that some authors are avoiding the operator

![]() in fractional differential equations

(see e.g. [112, 101, 84, 111, 7, 82]

or chapters in this volume).

[45.2.2] In their notation the eigenvalue equation

(2.133) becomes (c.f.[112, eq.(22)])

in fractional differential equations

(see e.g. [112, 101, 84, 111, 7, 82]

or chapters in this volume).

[45.2.2] In their notation the eigenvalue equation

(2.133) becomes (c.f.[112, eq.(22)])

| (2.135) |

containing two derivative operators instead of one.