7 Results

[635.1.1] The time evolution of almost invariant states can

be defined by the addition of random recurrence times.

[635.1.2] Let ![]() be the probability density of the sum

be the probability density of the sum

| (40) |

of ![]() independent

and identically-distributed random

recurrence times

independent

and identically-distributed random

recurrence times ![]() .

[635.1.3] Let

.

[635.1.3] Let ![]() from Equation (39)

be the common probability density of all

from Equation (39)

be the common probability density of all ![]() .

[635.1.4] Then, with

.

[635.1.4] Then, with ![]() and

and ![]() ,

,

| (41) |

is an ![]() -fold convolution of the discrete

recurrence time density in Equation (39).

[635.1.5] The family of distributions

-fold convolution of the discrete

recurrence time density in Equation (39).

[635.1.5] The family of distributions ![]() obeys

obeys

| (42) |

for all ![]() , and the discrete analogue of

Equation (5)

, and the discrete analogue of

Equation (5)

| (43) |

holds for all ![]() .

[635.1.6] Because the individual states in

.

[635.1.6] Because the individual states in ![]() are indistinguishable

within the given accuracy

are indistinguishable

within the given accuracy ![]() , but may evolve very

differently in time, it is natural to define the duration

of time needed for the first recurrence (a single time step) as an average

, but may evolve very

differently in time, it is natural to define the duration

of time needed for the first recurrence (a single time step) as an average

| (44) |

over recurrence times.

[635.1.7] If a macroscopic time evolution with a rescaled

time exists, then one has to rescale the sums

![]() and the iterations

and the iterations

| (45) |

in the limit ![]() with suitable norming constants

with suitable norming constants ![]() .

.

Theorem 3.

[635.1.8] Let ![]() be the probability density of

be the probability density of ![]() specified above in (41).

[635.1.9] If the distributions of

specified above in (41).

[635.1.9] If the distributions of ![]() converge

to a limit as

converge

to a limit as ![]() for suitable norming constants

for suitable norming constants ![]() ,

then there exist constants

,

then there exist constants ![]() and

and ![]() ,

such that

,

such that

| (46) |

[page 636, §0] where:

| (47) |

if ![]() diverges, while

diverges, while

| (48) |

if ![]() converges.

[636.0.1] For

converges.

[636.0.1] For ![]() , the function

, the function ![]() is

is ![]() .

[636.0.2] For

.

[636.0.2] For ![]() , the function

, the function ![]() for

for ![]() and

and

| (49) |

for ![]() .

.

Proof.

[636.1.1] The existence of a limiting distribution for ![]() is known to be equivalent to the stability of the limit [18].

[636.1.2] If the limit distribution is nondegenerate,

this implies that

the rescaling constants

is known to be equivalent to the stability of the limit [18].

[636.1.2] If the limit distribution is nondegenerate,

this implies that

the rescaling constants ![]() have the form

have the form

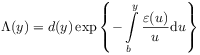

| (50) |

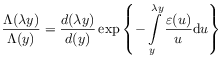

where ![]() is a slowly varying function [19],

defined by the requirement that

is a slowly varying function [19],

defined by the requirement that

| (51) |

holds for all ![]() .

[636.1.3] That the number

.

[636.1.3] That the number ![]() obeys Equation (47)

is proven in [18] (p. 179).

[636.1.4] It is bounded

as

obeys Equation (47)

is proven in [18] (p. 179).

[636.1.4] It is bounded

as ![]() , because the rescaled random

variables

, because the rescaled random

variables ![]() are positive.

are positive.

[636.2.1] To prove Equation (46), note that

the characteristic function of ![]() is

the

is

the ![]() -th power

-th power

| (52) |

because the characteristic functions

![]() of

of ![]() are identical for all

are identical for all ![]() .

[636.2.2] Inverse Fourier transformation gives:

.

[636.2.2] Inverse Fourier transformation gives:

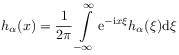

![\displaystyle p_{N}(k)=\frac{1}{2\pi}\int\limits _{{-\pi}}^{{\pi}}\mathrm{e}^{{-\mathrm{i}\xi k}}\left[p(\xi)\right]^{N}\mathrm{d}\xi=\frac{\tau}{2\pi D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}\int\limits _{{-\pi D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}}^{{\pi D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}}\mathrm{e}^{{-\mathrm{i}\xi x}}\left[p\left(\frac{\xi\tau}{D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}\right)\right]^{N}\mathrm{d}\xi](mi/mi269.png) |

(53) |

where:

| (54) |

and ![]() was substituted with

was substituted with ![]() .

[636.2.3] Let

.

[636.2.3] Let ![]() denote the characteristic function of

denote the characteristic function of

![]() , so that

, so that

|

(55) |

holds.

[page 637, §1]

[637.1.1] Following [20],

the difference ![]() in (46) can be

decomposed and bounded from above as

in (46) can be

decomposed and bounded from above as

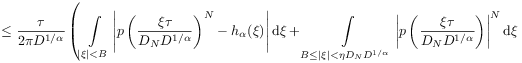

![\displaystyle=\frac{\tau}{2\pi D^{{1/\alpha}}}\left|\int\limits _{{-\pi D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}}^{{\pi D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}}\mathrm{e}^{{-\mathrm{i}\xi x}}\left[p\left(\frac{\xi\tau}{D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}\right)\right]^{N}\mathrm{d}\xi-\int\limits _{{-\infty}}^{{\infty}}\mathrm{e}^{{-\mathrm{i}\xi x}}\ h_{\alpha}(\xi)\mathrm{d}\xi\right|](mi/mi239.png) |

|||

![\displaystyle=\frac{\tau}{2\pi D^{{1/\alpha}}}\left|\;\int\limits _{{|\xi|<B}}\mathrm{e}^{{-\mathrm{i}\xi x}}\left[p\left(\frac{\xi\tau}{D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}\right)^{N}-h_{\alpha}(\xi)\right]\mathrm{d}\xi+\int\limits _{{B\leq|\xi|<\eta D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}}\mathrm{e}^{{-\mathrm{i}\xi x}}\left[p\left(\frac{\xi\tau}{D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}\right)^{N}-h_{\alpha}(\xi)\right]\mathrm{d}\xi\right.](mi/mi346.png) |

|||

![\displaystyle\qquad\left.+\int\limits _{{\eta\leq\frac{|\xi|}{D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}<\pi}}\mathrm{e}^{{-\mathrm{i}\xi x}}\left[p\left(\frac{\xi\tau}{D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}\right)^{N}-h_{\alpha}(\xi)\right]\mathrm{d}\xi-\int\limits _{{|\xi|\geq\pi D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}}\mathrm{e}^{{-\mathrm{i}\xi x}}\ h_{\alpha}(\xi)\mathrm{d}\xi\right|](mi/mi265.png) |

|||

|

|||

|

(56) |

with constants ![]() to be specified below.

[637.1.2] The terms involving

to be specified below.

[637.1.2] The terms involving ![]() from the second and third

integral have been absorbed in the fourth integral.

[637.1.3] The four integrals are now discussed further individually.

from the second and third

integral have been absorbed in the fourth integral.

[637.1.3] The four integrals are now discussed further individually.

[637.2.1] The first integral converges uniformly to zero for

![]() , because

, because

![]() belongs to the domain of attraction

of a stable law with index

belongs to the domain of attraction

of a stable law with index ![]() , as already noted above.

, as already noted above.

[637.3.1] To estimate the second integral, note that the characteristic

function ![]() belongs to the domain of attraction

for index

belongs to the domain of attraction

for index ![]() if and only if it behaves for

if and only if it behaves for ![]() as [20]

as [20]

| (57) |

where ![]() and

and ![]() is a slowly varying function at infinity obeying

is a slowly varying function at infinity obeying

| (58) |

[637.3.2] By the representation

theorem for slowly varying functions ([21] p. 12),

there exist functions ![]() and

and ![]() ,

such that the function

,

such that the function ![]() can be represented as

can be represented as

|

(59) |

[page 638, §0]

for some ![]() where

where ![]() is measurable and

is measurable and

![]() , as well as

, as well as ![]() hold for

hold for ![]() .

[638.0.1] As a consequence

.

[638.0.1] As a consequence

|

(60) |

so that with ![]() and

and ![]()

| (61) |

is obtained for ![]() .

[638.0.2] Therefore, there exists for any

.

[638.0.2] Therefore, there exists for any ![]() a positive number

a positive number

![]() independent of

independent of ![]() , such that

, such that

| (62) |

for sufficiently large ![]() .

[638.0.3] If

.

[638.0.3] If ![]() is sufficiently large,

it is then possible to choose an

is sufficiently large,

it is then possible to choose an ![]() (and find

(and find ![]() ), such that

), such that

|

(63) |

and this converges to zero for ![]() .

.

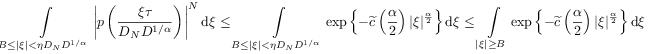

[638.1.1] The third integral is estimated by noting that

![]() for

for ![]() .

[638.1.2] Hence, there is a positive constant

.

[638.1.2] Hence, there is a positive constant ![]() , such that

, such that

| (64) |

for ![]() .

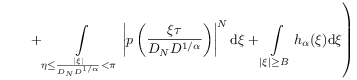

[638.1.3] Consequently, with Equation (50),

.

[638.1.3] Consequently, with Equation (50),

![\displaystyle\int\limits _{{\eta\leq\frac{|\xi|}{D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}<\pi}}\left|p\left(\frac{\xi\tau}{D_{N}D^{{1/\alpha}}}\right)\right|^{N}\mathrm{d}\xi\leq 2\pi\mathrm{e}^{{-cN}}\left[N\Lambda(N)D\right]^{{1/\alpha}}](mi/mi250.png) |

(65) |

converges to zero as ![]() .

.

[638.3.1] Equation (46) implies

| (66) |

for sufficiently large ![]() and all

and all ![]() .

[638.3.2] Inserting this into Equation (45) gives

.

[638.3.2] Inserting this into Equation (45) gives

| (67) |

[page 639, §0]

[639.0.1] For ![]() , the average return time

, the average return time

![]() is proportional to the discretization

is proportional to the discretization ![]() .

[639.0.2] In the case

.

[639.0.2] In the case ![]() , the average

time

, the average

time ![]() for return into

the set

for return into

the set ![]() in a single step diverges.

[639.0.3] This suggests an infinite rescaling of time as

in a single step diverges.

[639.0.3] This suggests an infinite rescaling of time as ![]() for

for ![]() .

[639.0.4] This rescaling of time combined with

.

[639.0.4] This rescaling of time combined with

![]() was called the ultra-long-time limit in [22].

[639.0.5] In the ultra-long-time limit

was called the ultra-long-time limit in [22].

[639.0.5] In the ultra-long-time limit ![]() with:

with:

| (68) |

one finds from Equation (67) the result

![\displaystyle\lim _{{{\tau\to\infty,N\to\infty}\atop{[N\Lambda(N)D]^{{1/\alpha}}/\tau=a}}}\mathscr{S}^{{-N}}\approx\sum _{{k=1}}^{\infty}h_{\alpha}\left(\frac{k}{a}\right)\;\mathscr{T}^{{-ka}}\;\frac{[k-(k-1)]}{a}\approx\int\limits _{0}^{\infty}h_{\alpha}\left(x\right)\;\mathscr{T}^{{-xa}}\;\mathrm{d}x](mi/mi257.png) |

(69) |

for sufficiently large ![]() and

and ![]() .

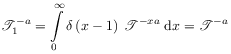

[639.0.6] The limit gives rise to

a family of one-parameter semigroups

.

[639.0.6] The limit gives rise to

a family of one-parameter semigroups ![]() (with family index

(with family index ![]() and parameter

and parameter ![]() )

of ultra-long-time evolution operators

)

of ultra-long-time evolution operators

![\displaystyle\lim _{{{\tau\to\infty,N\to\infty}\atop{[N\Lambda(N)D]^{{1/\alpha}}/\tau=a}}}\mathscr{S}^{{-N}}=\mathscr{T}^{{-a}}_{{\alpha}}=\int\limits _{0}^{\infty}h_{\alpha}\left(x\right)\;\mathscr{T}^{{-xa}}\;\mathrm{d}x](mi/mi256.png) |

(70) |

which are convolutions instead of translations.

[639.0.7] Note that

![]() because

because

![]() and

and ![]() .

[639.0.8] The rescaled age evolutions

.

[639.0.8] The rescaled age evolutions ![]() are called fractional time evolutions, because

their infinitesimal generators are

fractional time derivatives [22, 23].

are called fractional time evolutions, because

their infinitesimal generators are

fractional time derivatives [22, 23].

[639.1.1] The result shows that a proper mathematical

formulation of local stationarity requires a generalization of the

left-hand side in Equation (1), because

Equation (1) assumes implicitly a translation along the orbit.

[639.1.2] In general, the integration of infinitesimal

system changes leads to convolutions instead

of just translations along the orbit [22, 23].

[639.1.3] Of course, translations are a special case of

convolutions, to which they reduce in the

case when the parameter ![]() approaches unity.

[639.1.4] For

approaches unity.

[639.1.4] For ![]() , one finds

, one finds

| (71) |

and therefore

|

(72) |

is a right translation.

[639.1.5] Here, ![]() is an age or duration.

[639.1.6] This shows that also the special case of

induced right translations does not give

a group, but only a semigroup.

is an age or duration.

[639.1.6] This shows that also the special case of

induced right translations does not give

a group, but only a semigroup.